Function Vectors#

ARENA Function Vectors & Model Steering Tutorial

This tutorial is adapted from the ARENA program material and serves as a fantastic introduction to running experiments in NNsight and working with function vectors and model steering. Thanks to Callum McDougall for writing this comprehensive tutorial and for allowing us to adapt the tutorial for NNsight users, and thanks to Eric Todd for writing the original function vector paper!

ARENA: Streamlit Page

You can collapse each section so only the headers are visible, by clicking the arrow symbol on the left hand side of the markdown header cells.

Introduction#

These exercises serve as an exploration of the following question: can we steer a model to produce different outputs / have a different behaviour, by intervening on the model’s forward pass using vectors found by non gradient descent-based methods?

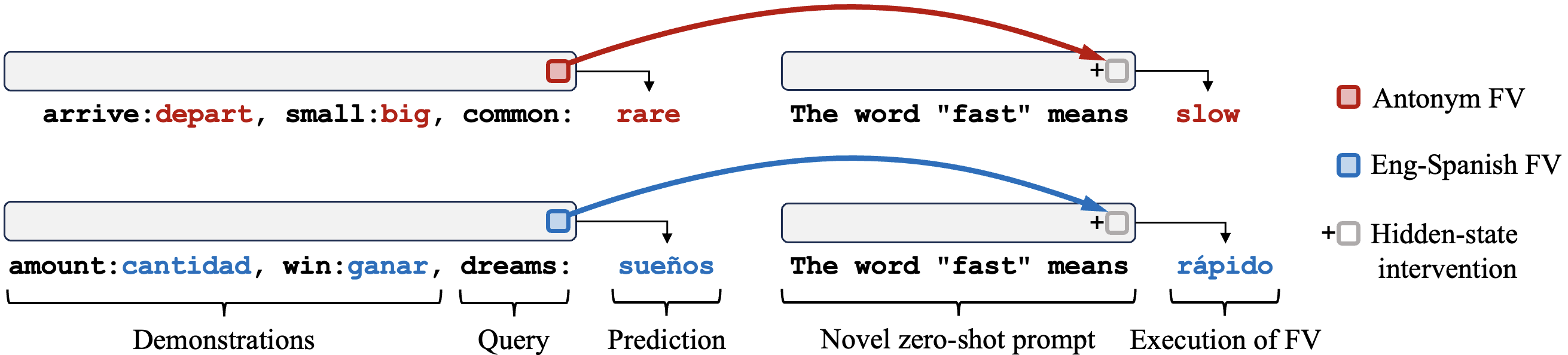

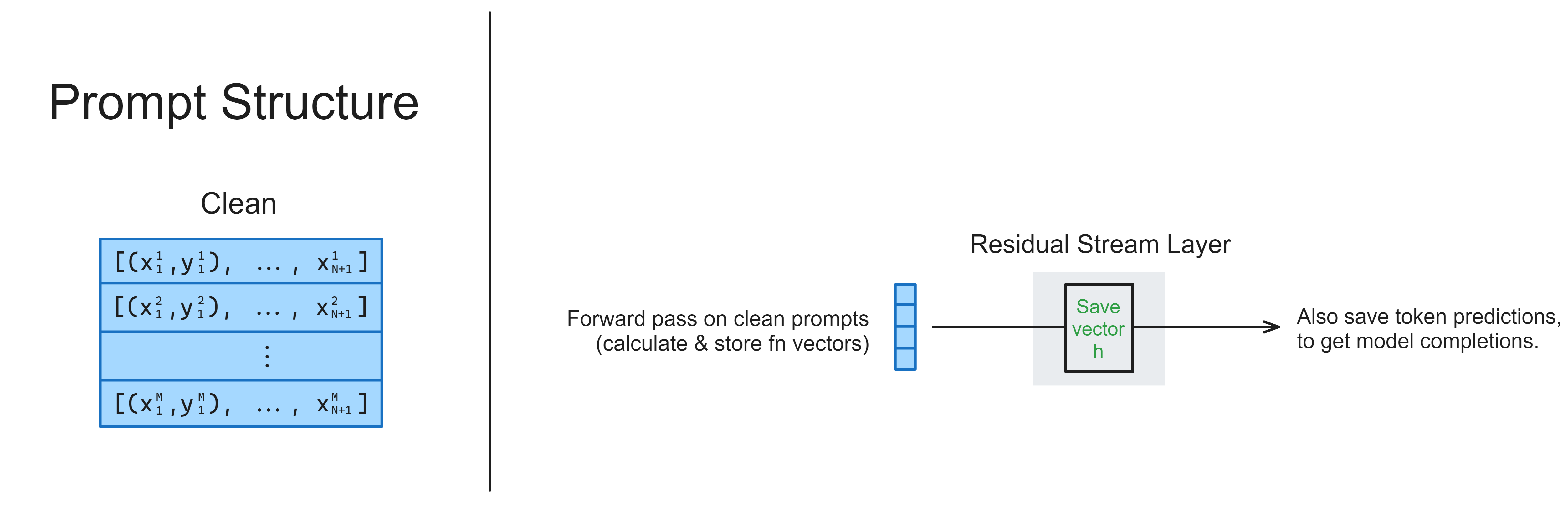

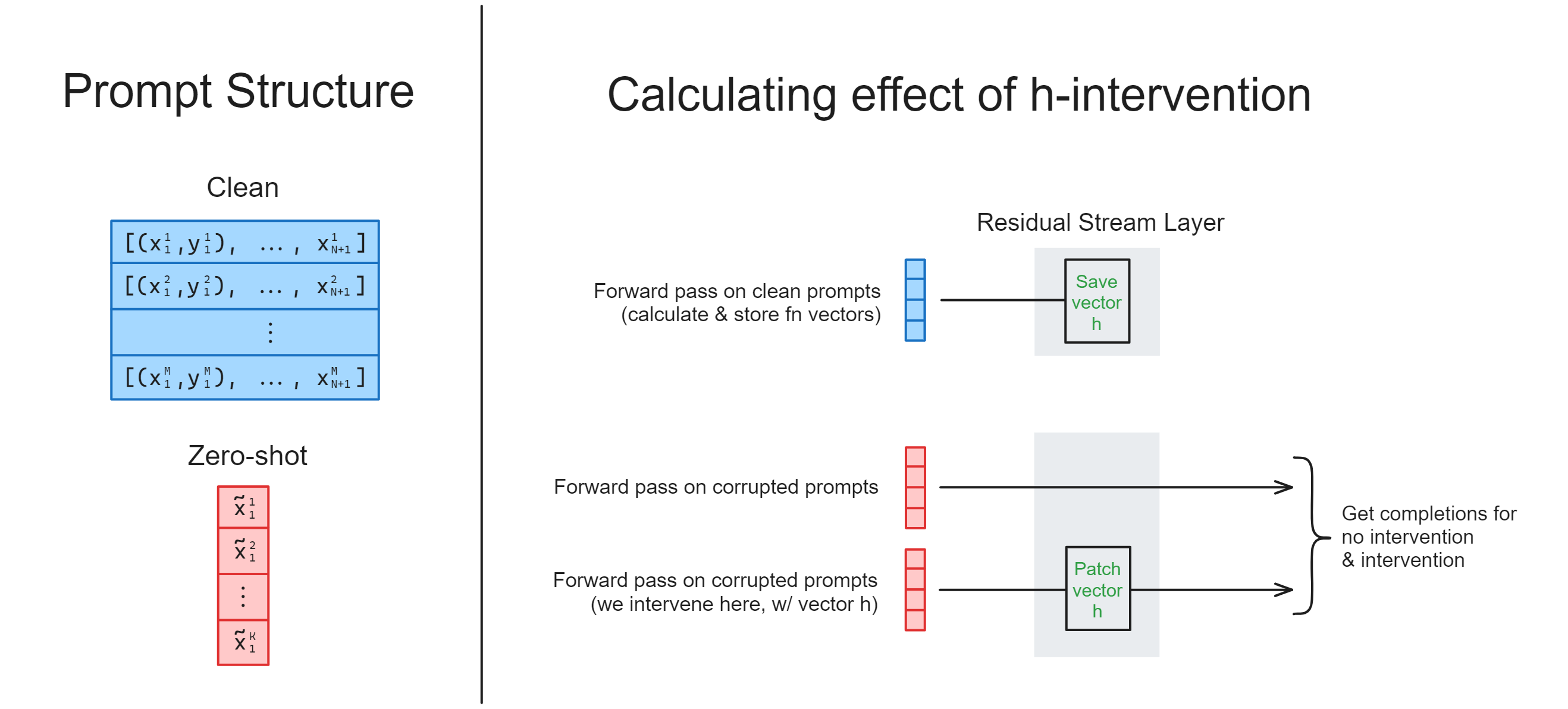

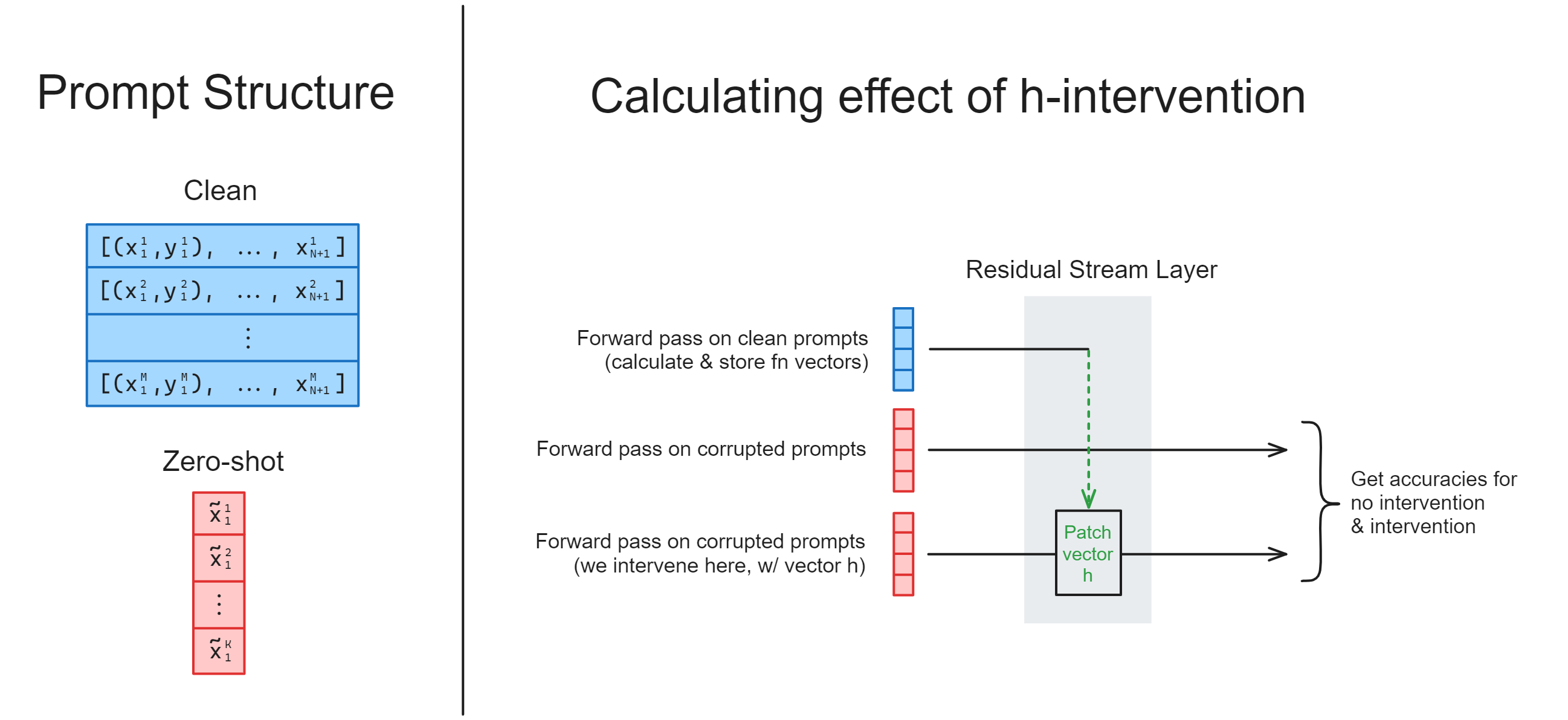

The majority of the exercises focus on function vectors: vectors which are extracted from forward passes on in-context learning (ICL) tasks, and added to the residual stream in order to trigger the execution of this task from a zero-shot prompt. The diagram below illustrates this.

The exercises also take you through use of the nnsight library, which is designed to support this kind of work (and other interpretability research) on very large language models - i.e. larger than models like GPT2-Small which you might be used to at this point in the course.

The final set of exercises look at Alex Turner et al’s work on steering vectors, which is conceptually related but has different aims and methodologies.

Content & Learning Objectives#

1️⃣ Introduction to nnsight#

In this section, you’ll learn the basics of how to use the nnsight library: running forward passes on your model, and saving the internal states. You’ll also learn some basics of HuggingFace models which translate over into nnsight models (e.g. tokenization, and how to work with model output).

Learning Objectives

Learn the basics of the

nnsightlibrary, and what it can be useful forLearn some basics of HuggingFace models (e.g. tokenization, model output)

Use it to extract & visualise GPT-J-6B’s internal activations

3️⃣ Function Vectors#

In this section, we’ll replicate the crux of the paper’s results, by identifying a set of attention heads whose outputs have a large effect on the model’s ICL performance, and showing we can patch with these vectors to induce task-solving behaviour on randomly shuffled prompts.

We’ll also learn how to use nnsight for multi-token generation, and steer the model’s behaviour. There exist exercises where you can try this out for different tasks, e.g. the Country-Capitals task, where you’ll be able to steer the model to complete prompts like "When you think of Netherlands, you usually think of" by talking about Amsterdam.

(Note - this section structurally follows sections 2.2, 2.3 and some of section 3 from the function vectors paper).

Learning Objectives

Define a metric to measure the causal effect of each attention head on the correct performance of the in-context learning task

Understand how to rearrange activations in a model during an

nnsightforward pass, to extract activations corresponding to a particular attention headLearn how to use

nnsightfor multi-token generation

4️⃣ Steering Vectors in GPT2-XL#

Here, we discuss a different but related set of research: Alex Turner’s work on steering vectors. This also falls under the umbrella of “interventions in the residual stream using vectors found with forward pass (non-SGD) based methods in order to alter behaviour”, but it has a different setup, objectives, and approach.

Learning Objectives

Understand the goals & main results from Alex Turner et al’s work on steering vectors

Reproduce the changes in behaviour described in their initial post

☆ Bonus#

Lastly, we discuss some possible extensions of function vectors & steering vectors work, which is currently an exciting area of development (e.g. with a paper on steering Llama 2-13b coming out as recently as December 2023).

Setup code#

[ ]:

import os

import sys

from pathlib import Path

IN_COLAB = "google.colab" in sys.modules

chapter = "chapter1_transformer_interp"

repo = "ARENA_3.0"

branch = "main"

# Install dependencies

try:

import nnsight

except:

%pip install openai>=1.56.2 nnsight einops jaxtyping plotly transformer_lens==2.11.0 git+https://github.com/callummcdougall/CircuitsVis.git#subdirectory=python gradio typing-extensions

%pip install --upgrade pydantic

# Get root directory, handling 3 different cases: (1) Colab, (2) notebook not in ARENA repo, (3) notebook in ARENA repo

root = (

"/content"

if IN_COLAB

else "/root"

if repo not in os.getcwd()

else str(next(p for p in Path.cwd().parents if p.name == repo))

)

if Path(root).exists() and not Path(f"{root}/{chapter}").exists():

if not IN_COLAB:

!sudo apt-get install unzip

%pip install jupyter ipython --upgrade

if not os.path.exists(f"{root}/{chapter}"):

!wget -P {root} https://github.com/callummcdougall/ARENA_3.0/archive/refs/heads/{branch}.zip

!unzip {root}/{branch}.zip '{repo}-{branch}/{chapter}/exercises/*' -d {root}

!mv {root}/{repo}-{branch}/{chapter} {root}/{chapter}

!rm {root}/{branch}.zip

!rmdir {root}/{repo}-{branch}

if f"{root}/{chapter}/exercises" not in sys.path:

sys.path.append(f"{root}/{chapter}/exercises")

os.chdir(f"{root}/{chapter}/exercises")

[ ]:

! pip install circuitsvis

! pip install plotly

! pip install jaxtyping

! pip install nnsight

[6]:

import logging

import os

import sys

import time

from collections import defaultdict

from pathlib import Path

import circuitsvis as cv

import einops

import numpy as np

import torch as t

from IPython.display import display

from jaxtyping import Float

from nnsight import CONFIG, LanguageModel

from openai import OpenAI

from rich import print as rprint

from rich.table import Table

from torch import Tensor

# Hide some info logging messages from nnsight

logging.disable(sys.maxsize)

t.set_grad_enabled(False)

device = t.device("mps" if t.backends.mps.is_available() else "cuda" if t.cuda.is_available() else "cpu")

# Make sure exercises are in the path

chapter = "chapter1_transformer_interp"

section = "part42_function_vectors_and_model_steering"

root_dir = next(p for p in Path.cwd().parents if (p / chapter).exists())

exercises_dir = root_dir / chapter / "exercises"

section_dir = exercises_dir / section

import part42_function_vectors_and_model_steering.solutions as solutions

import part42_function_vectors_and_model_steering.tests as tests

from plotly_utils import imshow

MAIN = __name__ == "__main__"

1️⃣ Introduction to nnsight#

Learning Objectives

Learn the basics of the

nnsightlibrary, and what it can be useful forLearn some basics of HuggingFace models (e.g. tokenization, model output)

Use it to extract & visualise GPT-J-6B’s internal activations

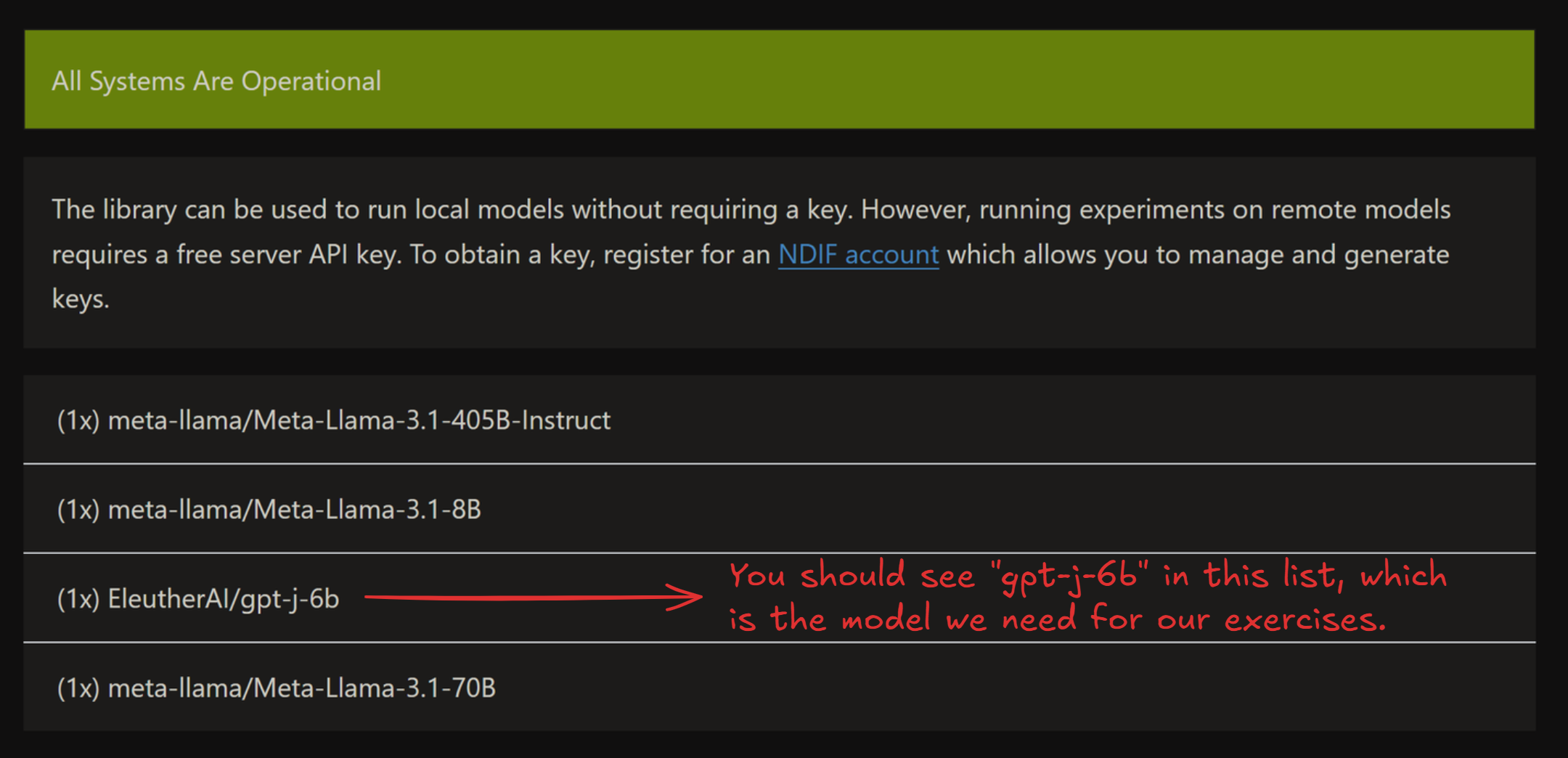

Remote execution#

We’ll start by discussing remote execution - the ability nnsight has to run models on an external server, which is one of the major benefits of the library as a research tool. This helps you bypass the memory & computational limits you might be faced with on your own machine. For remote execution to work, you need 2 things:

An API key from the NDIF login page, which you can request here

The model you’re working with being live - you can see all live models in the status page here

Note that the status page sometimes takes ~5 minutes to load all live models - click the dropdown below to see an example of what the status page should look like once the models have loaded. If you can’t see the model you’re looking for in this list, then you should set REMOTE=False for these exercises, or else make a request on the NDIF Discord to get the model live.

Example status page

Important syntax#

Here, we’ll discuss some important syntax for interacting with nnsight models. Since these models are extensions of HuggingFace models, some of this information (e.g. tokenization) applies to plain HuggingFace models as well as nnsight models, and some of it (e.g. forward passes) is specific to nnsight, i.e. it would work differently if you just had a standard HuggingFace model. Make sure to keep this distinction in mind, otherwise syntax can get confusing!

Model config#

Each model comes with a model.config, which contains lots of useful information about the model (e.g. number of heads and layers, size of hidden layers, etc.). You can access this with model.config. Run the code below to see this in action, and to define some useful variables for later.

[7]:

model = LanguageModel("EleutherAI/gpt-j-6b", device_map="auto", torch_dtype=t.bfloat16)

tokenizer = model.tokenizer

N_HEADS = model.config.n_head

N_LAYERS = model.config.n_layer

D_MODEL = model.config.n_embd

D_HEAD = D_MODEL // N_HEADS

print(f"Number of heads: {N_HEADS}")

print(f"Number of layers: {N_LAYERS}")

print(f"Model dimension: {D_MODEL}")

print(f"Head dimension: {D_HEAD}\n")

print("Entire config: ", model.config)

Number of heads: 16

Number of layers: 28

Model dimension: 4096

Head dimension: 256

Entire config: GPTJConfig {

"activation_function": "gelu_new",

"architectures": [

"GPTJForCausalLM"

],

"attn_pdrop": 0.0,

"bos_token_id": 50256,

"embd_pdrop": 0.0,

"eos_token_id": 50256,

"gradient_checkpointing": false,

"initializer_range": 0.02,

"layer_norm_epsilon": 1e-05,

"model_type": "gptj",

"n_embd": 4096,

"n_head": 16,

"n_inner": null,

"n_layer": 28,

"n_positions": 2048,

"resid_pdrop": 0.0,

"rotary": true,

"rotary_dim": 64,

"scale_attn_weights": true,

"summary_activation": null,

"summary_first_dropout": 0.1,

"summary_proj_to_labels": true,

"summary_type": "cls_index",

"summary_use_proj": true,

"task_specific_params": {

"text-generation": {

"do_sample": true,

"max_length": 50,

"temperature": 1.0

}

},

"tie_word_embeddings": false,

"tokenizer_class": "GPT2Tokenizer",

"torch_dtype": "bfloat16",

"transformers_version": "4.51.3",

"use_cache": true,

"vocab_size": 50400

}

Tokenizers#

A model comes with a tokenizer, accessable with model.tokenizer (just like TransformerLens). Unlike TransformerLens, we won’t be using utility functions like model.to_str_tokens, instead we’ll be using the tokenizer directly. Some important functions for today’s exercises are:

tokenizer(i.e. just calling it on some input)This takes in a string (or list of strings) and returns the tokenized version.

It will return a dictionary, always containing

input_ids(i.e. the actual tokens) but also other things which are specific to the transformer model (e.g.attention_mask- see dropdown).Other useful arguments for this function:

return_tensors- if this is"pt", you’ll get results returned as PyTorch tensors, rather than lists (which is the default).padding- if True (default is False), the tokenizer can accept sequences of variable length. The shorter sequences get padded at the beginning (see dropdown below for more).

tokenizer.decodeThis takes in tokens, and returns the decoded string.

If the input is an integer, it returns the corresponding string. If the input is a list / 1D array of integers, it returns all those strings concatenated (which can sometimes not be what you want).

tokenizer.batch_decodeEquivalent to

tokenizer.decode, but it doesn’t concatenate.If the input is a list / 1D integer array, it returns a list of strings. If the input is 2D, it will concatenate within each list.

tokenizer.tokenizeTakes in a string, and returns a list of strings.

Run the code below to see some examples of these functions in action.

[8]:

# Calling tokenizer returns a dictionary, containing input ids & other data.

# If returned as a tensor, then by default it will have a batch dimension.

print(tokenizer("This must be Thursday", return_tensors="pt"))

# Decoding a list of integers, into a concatenated string.

print(tokenizer.decode([40, 1239, 714, 651, 262, 8181, 286, 48971, 12545, 13]))

# Using batch decode, on both 1D and 2D input.

print(tokenizer.batch_decode([4711, 2456, 481, 307, 6626, 510]))

print(tokenizer.batch_decode([[1212, 6827, 481, 307, 1978], [2396, 481, 428, 530]]))

# Split sentence into tokens (note we see the special Ġ character in place of prepended spaces).

print(tokenizer.tokenize("This sentence will be tokenized"))

{'input_ids': tensor([[1212, 1276, 307, 3635]]), 'attention_mask': tensor([[1, 1, 1, 1]])}

I never could get the hang of Thursdays.

['These', ' words', ' will', ' be', ' split', ' up']

['This sentence will be together', 'So will this one']

['This', 'Ġsentence', 'Ġwill', 'Ġbe', 'Ġtoken', 'ized']

Note on attention_mask (optional)

attention_mask, which is a series of 1s and 0s. We mask attention at all 0-positions (i.e. we don’t allow these tokens to be attended to). This is useful when you have to do padding. For example:

model.tokenizer(["Hello world", "Hello"], return_tensors="pt", padding=True)

will return:

{

'attention_mask': tensor([[1, 1], [0, 1]]),

'input_ids': tensor([[15496, 995], [50256, 15496]])

}

We can see how the shorter sequence has been padded at the beginning, and attention to this token will be masked.

Model outputs#

At a high level, there are 2 ways to run our model: using the trace method (a single forward pass) and the generate method (generating multiple tokens). We’ll focus on trace for now, and we’ll discuss generate when it comes to multi-token generation later.

The default behaviour of forward passes in normal HuggingFace models is to return an object containing logits (and optionally a bunch of other things). The default behaviour of trace in nnsight is to not return anything, because anything that we choose to return is explicitly returned inside the context manager.

Below is the simplest example of code to run the model (and also access the internal states of the model). Run it and look at the output, then read the explanation below. Remember to obtain and set an API key first if you’re using remote execution!

[19]:

REMOTE = True

if IN_COLAB:

# include your HuggingFace Token and NNsight API key on Colab secrets

from google.colab import userdata

NDI F_API = userdata.get('NDIF_API')

CONFIG.set_default_api_key(NDIF_API)

prompt = "The Eiffel Tower is in the city of"

with model.trace(prompt, remote=REMOTE):

# Save the model's hidden states

hidden_states = model.transformer.h[-1].output[0].save()

# Save the model's logit output

logits = model.lm_head.output[0, -1].save()

# Get the model's logit output, and it's next token prediction

print(f"logits.shape = {logits.shape} = (vocab_size,)")

print("Predicted token ID =", predicted_token_id := logits.argmax().item())

print(f"Predicted token = {tokenizer.decode(predicted_token_id)!r}")

# Print the shape of the model's residual stream

print(f"\nresid.shape = {hidden_states.shape} = (batch_size, seq_len, d_model)")

logits.shape = torch.Size([50400]) = (vocab_size,)

Predicted token ID = 6342

Predicted token = ' Paris'

resid.shape = torch.Size([1, 10, 4096]) = (batch_size, seq_len, d_model)

Lets go over this piece by piece.

First, we create a context block by calling .trace(...) on the model object. This denotes that we wish to generate tokens given some prompts.

with model.trace(prompt, remote=REMOTE):

By default, running this will cause your model to be loaded & run locally, but by passing remote=REMOTE, it causes the model to be run on the server instead. This is very useful when working with models too large to fit on your machine (or even models which can fit on your machine, but run slowly due to their size, however if you’re running this material on a sufficiently large GPU, you may prefer to set REMOTE=False). The input argument can take a variety of formats: strings, lists of

tokens, tensors of tokens, etc. Here, we’ve just used a string prompt.

The most interesting part of nnsight is the ability to access the model’s internal states (like you might already have done with TransformerLens). Let’s now see how this works!

hidden_states = model.transformer.h[-1].output[0]

On this line we’re saying: within our forward pass, access the last layer of the transformer model.transformer.h[-1], access this layer’s output .output (which is a tuple of tensors), index the first tensor in this tuple .output[0].

Let’s break down this line in a bit more detail:

model.transformer.h[-1]is a module in our transformer.If you

print(model), you’ll see that it consists oftransformerandlm_head(for “language modelling head”). Thetransformermodule is made up of embeddings & dropout, a series of layers (called.h, for “hidden states”), and a final layernorm. So indexing.h[-1]gives you the final layer.Note - it’s often useful to visit the documentation page for whatever model you’re working on, e.g. you can find GPT-J here. Not all models will have a nice uniform standardized architecture like you might be used to in TransformerLens!

.output[0]gives you this module’s output, as a proxy.The output of a module is often a tuple (again, you can see on the documentation page what the output of each module is). In this case, it’s a tuple of 2 tensors, the first of which is the actual layer output (the thing we want).

Doing operations on a proxy still returns a proxy - this is why we can index into the

outputproxy tuple and get a proxy tensor!

Optional exercise - we mentioned that .output returns a tuple of 2 tensors. Can you use the documentation page what the second tensor in this tuple is?

The second output is also a tuple of tensors, of length 2. In the GPT-J source code, they are called present. They represent the keys and values which were calculated in this forward pass (as opposed to those that were calculated in an earlier forward pass, and cached by the model). Since we’re only generating one new token, these are just the full keys and values.

The next command:

logits = model.lm_head.output[0, -1]

can be understood in a very similar way. The only difference is that we’re accessing the output of lm_head, the language modelling head (i.e. the unembedding at the very end), and the output is just a tensor of shape (batch, seq, d_vocab) rather than a tuple of tensors. Again, see the documentation page for this.

If you’ve worked with Hugging Face models then you might be used to getting logits directly from the model output, but here we generally extract logits from the model internals just like any other activation because this allows us to control exactly what we return. If we return lots of very large tensors, this can take quite a while to download from the server (remember that d_vocab is often very large for transformers, i.e. around 50k). See the “which objects to save” section below for

more discussion on this.

Output vs input#

You can also extract a module’s input using .input or .inputs. If a module’s forward method is called as module.forward(*args, **kwargs) then .inputs returns a tuple of (tuple_of_args, dict_of_kwargs). Alternatively, .input is an alias for .inputs[0][0], in other words it returns the first arg from the module’s forward method (which is usually the tensor we want).

Remember that if you’re not sure then you can debug with print(module.input.shape) - even if .inputs is a tuple of inputs, this will work to recursively print the shape of all the tensors in the tuple, rather than causing an error.

Which objects to save#

Note that we saved logits above, which is a vector of length 50k. In general, it’s best to save as small an object as possible, because this reduces the size of object you’ll have to download from the server. For example, if you only want the next token completions, just argmax the logits and then save the result! All basic tensor operations can be performed within your context manager.

Scan & Validate#

A really cool feature in nnsight is the scan & validate mode, which allows you to efficiently debug without getting long uninterpretable error messages. For example, consider the code below, which tries to zero ablate one of the model’s output tensors. Can you figure out what’s wrong with it before running it?

[20]:

seq_len = len(model.tokenizer.encode(prompt))

try:

with model.trace(prompt, remote=REMOTE):

original_output = model.transformer.h[-1].output[0].clone()

model.transformer.h[-1].output[0][:, seq_len] = 0

modified_output = model.transformer.h[-1].output[0].save()

except Exception as e:

print(f"Uninformative error message:\n {e.__class__.__name__}: {e}")

Uninformative error message:

NNsightError: index 10 is out of bounds for dimension 1 with size 10

If you guessed “we’re indexing a tensor along a dimension of size seq_len with index seq_len which is an indexing error, you’d be correct! But the error message we get is pretty opaque. This is because of the way the objects in nnsight work: they’re not tensors, they’re tensor proxies, and can behave in funny ways sometimes.

If we want to debug, we should instead pass scan=True and validate=True into our model.trace call. scan=True means we run “fake inputs” through the model which incur no memory costs, and so can be done very quickly and cheaply to detect errors. validate=True will run tests during our forward pass that make our error messages more informative. When we use both, we get fast no-memory-cost operations with interpretable error messages!

[21]:

try:

with model.trace(prompt, remote=REMOTE, scan=True, validate=True):

original_output = model.transformer.h[-1].output[0].clone()

print(f"{model.transformer.h[-1].output.shape=}\n")

model.transformer.h[-1].output[0][:, seq_len] = 0

modified_output = model.transformer.h[-1].output[0].save()

except Exception as e:

print(f"Informative error message:\n {e.__class__.__name__}: {e}")

model.transformer.h[-1].output.shape=(torch.Size([1, 10, 4096]), <transformers.cache_utils.DynamicCache object at 0x7edbe8693e50>)

Informative error message:

IndexError: index 10 is out of bounds for dimension 1 with size 10

It’s possible to use validate without using scan (e.g. if you have any assert proxy.shape == ... then you must use validate=True), although we generally recommend using both when debugging, and then neither when you’re finished debugging.

Also note that (as the example above shows) it’s useful to use scan=True, validate=True when printing tensor shapes, at the initial exploration phase, if you’re not exactly sure what the shape of a particular input / output will be. Even if your proxy objects are tuples of tensors, you can still call .shape, and it will return a tuple of the shapes of each tensor in the proxy!

Putting this into practice#

Exercise - visualize attention heads#

Difficulty: 🔴🔴⚪⚪⚪ Importance: 🔵🔵🔵⚪⚪ You should spend up to 10-20 minutes on this exercise.

We just covered a lot of content, so lets put it into practice. Your first task is to extract the attention patterns from the zeroth layer of the transformer, and visualize them using circuitsvis. As a reminder, the syntax for circuitsvis is:

cv.attention.attention_patterns(

tokens=tokens,

attention=attention,

)

where tokens is a list of strings, and attention is a tensor of shape (num_heads, num_tokens, num_tokens).

If you’re stuck, here’s a link to the source code for GPT-J. Look for how the attention patterns are calculated, within the GPTJAttention block.

Note - this model uses dropout on the attention probabilities, as you’ll probably notice from looking at the source code in the link above. This won’t affect the model’s behaviour because dropout is disabled in inference mode (and using the ``generate`` method always puts a model in inference mode). But it is still a layer which exists in the model, so you can access its input or output just like any other module.

Aside - inference mode

Dropout is one of the two main layers whose behaviour changes in inference mode (the other is BatchNorm).

If you want to run the model without inference mode, you can wrap your code in with model.trace(inference=False):. However, you don’t need to worry about this for the purposes of these exercises.

If you’re stuck on how to reference the right module, see the following hint:

Hint - what module you should get attention from

You want to extract attention from model.transformer.h[0].attn.attn_dropout.input. If you used .output, it would give you the same values (although they might differ by a dummy batch dimension). Both of these will return a single tensor, because dropout layers take just one input and return just one output.

Aside - GPT2 tokenizer uses special characters to represent space

GPT2 tokenizer uses “Ġ” to represent prepended space. So [“My”, ” name”, ” is”, ” James”] will be tokenized as [“My”, “Ġname”, “Ġis”, “ĠJames”]. Make sure you replace “Ġ” with an actual space.

[ ]:

# YOUR CODE HERE - extract and visualize attention

Solution (and explanation)

with model.trace(prompt, remote=REMOTE):

attn_patterns = model.transformer.h[0].attn.attn_dropout.input.save()

# Get string tokens (replacing special character for spaces)

str_tokens = model.tokenizer.tokenize(prompt)

str_tokens = [s.replace('Ġ', ' ') for s in str_tokens]

# Attention patterns (squeeze out the batch dimension)

attn_patterns_value = attn_patterns.squeeze(0)

print("Layer 0 Head Attention Patterns:")

display(cv.attention.attention_patterns(

tokens=str_tokens,

attention=attn_patterns_value,

))

Explanation:

Within the context managers:

We access the attention patterns by taking the input to the

attn_dropout.From the GPT-J source code, we can see that the attention weights are calculated by standard torch functions (and an unnamed

nn.Softmaxmodule) from the key and query vectors, and are then passed through the dropout layer before being used to calculate the attention layer output. So by accessing the input to the dropdown layer, we get the attention weights before dropout is applied.Because of the previously discussed point about dropout not working in inference mode, we could also use the output of

attn_dropout, and get the same values.

Outside of the context managers:

We use the

tokenizemethod to tokenize the prompt.

As an optional bonus exercise, you can verify for yourself that these are the correct attention patterns, by calculating them from scratch using the key and query vectors. Using model.transformer.h[0].attn.q_proj.output will give you the query vectors, and k_proj for the key vectors. However, one thing to be wary of is that GPT-J uses rotary embeddings, which makes the computation of attention patterns from keys and queries a bit harder than it would otherwise be. See

here for an in-depth discussion of rotary embeddings, and here for some rough intuitions.

2️⃣ Task-encoding hidden states#

Learning Objectives

Understand how

nnsightcan be used to perform causal interventions, and perform some yourselfReproduce the “h-vector results” from the function vectors paper; that the residual stream does contain a vector which encodes the task and can induce task behaviour on zero-shot prompts

We’ll begin with the following question, posed by the Function Vectors paper:

When a transformer processes an ICL (in-context-learning) prompt with exemplars demonstrating task :math:`T`, do any hidden states encode the task itself?

We’ll prove that the answer is yes, by constructing a vector \(h\) from a set of ICL prompts for the antonym task, and intervening with our vector to make our model produce antonyms on zero-shot prompts.

This will require you to learn how to perform causal interventions with nnsight, not just save activations.

Note - this section structurally follows section 2.1 of the function vectors paper.

ICL Task#

Exercise (optional) - generate your own antonym pairs#

Difficulty: 🔴🔴🔴🔴⚪ Importance: 🔵🔵⚪⚪⚪ If you choose to do this exercise, you should spend up to 10-30 minutes on it - depending on your familiarity with the OpenAI Python API.

We’ve provided you two options for the antonym dataset you’ll use in these exercises.

Firstly, we’ve provided you a list of word pairs, in the file

data/antonym_pairs.txt.Secondly, if you want to run experiments like the ones in this paper, it can be good practice to learn how to generate prompts from GPT-4 or other models (this is how we generated the data for this exercise).

If you just want to use the provided list of words, skip this exercise and run the code below to load in the dataset from the text file. Alternatively, if you want to generate your own dataset, you can fill in the function generate_dataset below, which should query GPT-4 and get a list of antonym pairs.

See here for a guide to using the chat completions API, if you haven’t already used it. Use the two dropdowns below (in order) for some guidance.

Getting started #1

Here is a recommended template:

client = OpenAI(api_key=api_key)

response = client.chat.completions.create(

model="gpt-4",

messages=[

{"role": "system", "content": "You are a helpful assistant."},

{"role": "user", "content": antonym_task},

{"role": "assistant", "content": start_of_response},

]

)

where antonym_task explains the antonym task, and start_of_respose gives the model a prompt to start from (e.g. “Sure, here are some antonyms: …”), to guide its subsequent behaviour.

Getting started #2

Here is an template you might want to use for the actual request:

example_antonyms = "old: young, top: bottom, awake: asleep, future: past, "

response = openai.ChatCompletion.create(

model="gpt-4",

messages=[

{"role": "system", "content": "You are a helpful assistant."},

{"role": "user", "content": f"Give me {N} examples of antonym pairs. They should be obvious, i.e. each word should be associated with a single correct antonym."},

{"role": "assistant", "content": f"Sure! Here are {N} pairs of antonyms satisfying this specification: {example_antonyms}"},

]

)

where N is the function argument. Note that we’ve provided a few example antonyms, and appended them to the start of GPT4’s completion. This is a classic trick to guide the rest of the output (in fact, it’s commonly used in adversarial attacks).

Note - it’s possible that not all the antonyms returned will be solvable by GPT-J. In this section, we won’t worry too much about this. When it comes to testing out our zero-shot intervention, we’ll make sure to only use cases where GPT-J can actually solve it.

[24]:

def generate_antonym_dataset(N: int):

"""

Generates 100 pairs of antonyms, in the form of a list of 2-tuples.

"""

assert os.environ.get("OPENAI_API_KEY", None) is not None, "Please set your API key before running this function!"

client = OpenAI(api_key=os.environ["OPENAI_API_KEY"])

response = client.chat.completions.create(

model="gpt-3.5-turbo",

messages=[

{"role": "system", "content": "You are a helpful assistant."},

{

"role": "user",

"content": f"Generate {N} pairs of antonyms in the form of a list of 2-tuples. For example, [['old', 'young'], ['top', bottom'], ['awake', 'asleep']...].",

},

{"role": "assistant", "content": "Sure, here is a list of 100 antonyms: "},

],

)

return response

if os.environ.get("OPENAI_API_KEY", None) is not None:

ANTONYM_PAIRS = generate_antonym_dataset(100)

# Save the word pairs in a text file

with open(section_dir / "data" / "my_antonym_pairs.txt", "w") as f:

for word_pair in ANTONYM_PAIRS:

f.write(f"{word_pair[0]} {word_pair[1]}\n")

# Load the word pairs from the text file

with open(section_dir / "data" / "antonym_pairs.txt", "r") as f:

ANTONYM_PAIRS = [line.split() for line in f.readlines()]

print(ANTONYM_PAIRS[:10])

[['old', 'young'], ['top', 'bottom'], ['awake', 'asleep'], ['future', 'past'], ['appear', 'disappear'], ['early', 'late'], ['empty', 'full'], ['innocent', 'guilty'], ['ancient', 'modern'], ['arrive', 'depart']]

ICL Dataset#

To handle this list of word pairs, we’ve given you some helpful classes.

Firstly, there’s the ICLSequence class, which takes in a list of word pairs and contains methods for constructing a prompt (and completion) from these words. Run the code below to see how it works.

[25]:

class ICLSequence:

"""

Class to store a single antonym sequence.

Uses the default template "Q: {x}\nA: {y}" (with separate pairs split by "\n\n").

"""

def __init__(self, word_pairs: list[list[str]]):

self.word_pairs = word_pairs

self.x, self.y = zip(*word_pairs)

def __len__(self):

return len(self.word_pairs)

def __getitem__(self, idx: int):

return self.word_pairs[idx]

def prompt(self):

"""Returns the prompt, which contains all but the second element in the last word pair."""

p = "\n\n".join([f"Q: {x}\nA: {y}" for x, y in self.word_pairs])

return p[: -len(self.completion())]

def completion(self):

"""Returns the second element in the last word pair (with padded space)."""

return " " + self.y[-1]

def __str__(self):

"""Prints a readable string representation of the prompt & completion (indep of template)."""

return f"{', '.join([f'({x}, {y})' for x, y in self[:-1]])}, {self.x[-1]} ->".strip(", ")

word_list = [["hot", "cold"], ["yes", "no"], ["in", "out"], ["up", "down"]]

seq = ICLSequence(word_list)

print("Tuple-representation of the sequence:")

print(seq)

print("\nActual prompt, which will be fed into the model:")

print(seq.prompt())

Tuple-representation of the sequence:

(hot, cold), (yes, no), (in, out), up ->

Actual prompt, which will be fed into the model:

Q: hot

A: cold

Q: yes

A: no

Q: in

A: out

Q: up

A:

Secondly, we have the ICLDataset class. This is also fed a word pair list, and it has methods for generating batches of prompts and completions. It can generate both clean prompts (where each pair is actually an antonym pair) and corrupted prompts (where the answers for each pair are randomly chosen from the dataset).

[26]:

class ICLDataset:

"""

Dataset to create antonym pair prompts, in ICL task format. We use random seeds for consistency

between the corrupted and clean datasets.

Inputs:

word_pairs:

list of ICL task, e.g. [["old", "young"], ["top", "bottom"], ...] for the antonym task

size:

number of prompts to generate

n_prepended:

number of antonym pairs before the single-word ICL task

bidirectional:

if True, then we also consider the reversed antonym pairs

corrupted:

if True, then the second word in each pair is replaced with a random word

seed:

random seed, for consistency & reproducibility

"""

def __init__(

self,

word_pairs: list[list[str]],

size: int,

n_prepended: int,

bidirectional: bool = True,

seed: int = 0,

corrupted: bool = False,

):

assert n_prepended + 1 <= len(word_pairs), "Not enough antonym pairs in dataset to create prompt."

self.word_pairs = word_pairs

self.word_list = [word for word_pair in word_pairs for word in word_pair]

self.size = size

self.n_prepended = n_prepended

self.bidirectional = bidirectional

self.corrupted = corrupted

self.seed = seed

self.seqs = []

self.prompts = []

self.completions = []

# Generate the dataset (by choosing random word pairs, and constructing `ICLSequence` objects)

for n in range(size):

np.random.seed(seed + n)

random_pairs = np.random.choice(len(self.word_pairs), n_prepended + 1, replace=False)

# Randomize the order of each word pair (x, y). If not bidirectional, we always have x -> y not y -> x

random_orders = np.random.choice([1, -1], n_prepended + 1)

if not (bidirectional):

random_orders[:] = 1

word_pairs = [self.word_pairs[pair][::order] for pair, order in zip(random_pairs, random_orders)]

# If corrupted, then replace y with a random word in all (x, y) pairs except the last one

if corrupted:

for i in range(len(word_pairs) - 1):

word_pairs[i][1] = np.random.choice(self.word_list)

seq = ICLSequence(word_pairs)

self.seqs.append(seq)

self.prompts.append(seq.prompt())

self.completions.append(seq.completion())

def create_corrupted_dataset(self):

"""Creates a corrupted version of the dataset (with same random seed)."""

return ICLDataset(

self.word_pairs,

self.size,

self.n_prepended,

self.bidirectional,

corrupted=True,

seed=self.seed,

)

def __len__(self):

return self.size

def __getitem__(self, idx: int):

return self.seqs[idx]

You can see how this dataset works below. Note that the correct completions have a prepended space, because this is how the antonym prompts are structured - the answers are tokenized as "A: answer" -> ["A", ":", " answer"]. Forgetting prepended spaces is a classic mistake when working with transformers!

[27]:

dataset = ICLDataset(ANTONYM_PAIRS, size=10, n_prepended=2, corrupted=False)

table = Table("Prompt", "Correct completion")

for seq, completion in zip(dataset.seqs, dataset.completions):

table.add_row(str(seq), repr(completion))

rprint(table)

┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┓ ┃ Prompt ┃ Correct completion ┃ ┡━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┩ │ (right, left), (maximum, minimum), melt -> │ ' freeze' │ │ (minimum, maximum), (old, new), punishment -> │ ' reward' │ │ (arrogant, humble), (blunt, sharp), compulsory -> │ ' voluntary' │ │ (inside, outside), (freeze, melt), full -> │ ' empty' │ │ (reject, accept), (awake, asleep), dusk -> │ ' dawn' │ │ (invisible, visible), (punishment, reward), heavy -> │ ' light' │ │ (victory, defeat), (forward, backward), young -> │ ' old' │ │ (up, down), (compulsory, voluntary), right -> │ ' wrong' │ │ (open, closed), (domestic, foreign), brave -> │ ' cowardly' │ │ (under, over), (past, future), increase -> │ ' decrease' │ └──────────────────────────────────────────────────────┴────────────────────┘

Compare this output to what it looks like when corrupted=True. Each of the pairs before the last one has their second element replaced with a random one (but the last pair is unchanged).

[28]:

dataset = ICLDataset(ANTONYM_PAIRS, size=10, n_prepended=2, corrupted=True)

table = Table("Prompt", "Correct completion")

for seq, completions in zip(dataset.seqs, dataset.completions):

table.add_row(str(seq), repr(completions))

rprint(table)

┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┓ ┃ Prompt ┃ Correct completion ┃ ┡━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┩ │ (right, private), (maximum, destroy), melt -> │ ' freeze' │ │ (minimum, increase), (old, sharp), punishment -> │ ' reward' │ │ (arrogant, humble), (blunt, deep), compulsory -> │ ' voluntary' │ │ (inside, voluntary), (freeze, exterior), full -> │ ' empty' │ │ (reject, profit), (awake, start), dusk -> │ ' dawn' │ │ (invisible, birth), (punishment, spend), heavy -> │ ' light' │ │ (victory, rich), (forward, honest), young -> │ ' old' │ │ (up, lie), (compulsory, short), right -> │ ' wrong' │ │ (open, soft), (domestic, anxious), brave -> │ ' cowardly' │ │ (under, melt), (past, young), increase -> │ ' decrease' │ └───────────────────────────────────────────────────┴────────────────────┘

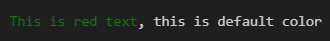

Aside - the rich library

The rich library is a helpful little library to display outputs more clearly in a Python notebook or terminal. It’s not necessary for this workshop, but it’s a nice little tool to have in your toolbox.

The most important function is rich.print (usually imported as rprint). This can print basic strings, but it also supports the following syntax for printing colors:

rprint("[green]This is green text[/], this is default color")

and for making text bold / underlined:

rprint("[u dark_orange]This is underlined[/], and [b cyan]this is bold[/].")

It can also print tables:

from rich.table import Table

table = Table("Col1", "Col2", title="Title") # title is optional

table.add_row("A", "a")

table.add_row("B", "b")

rprint(table)

The text formatting (bold, underlined, colors, etc) is also supported within table cells.

Task-encoding vector#

Exercise - forward pass on antonym dataset#

Difficulty: 🔴🔴⚪⚪⚪ Importance: 🔵🔵🔵⚪⚪ You should spend up to 10-15 minutes on this exercise.

You should fill in the calculate_h function below. It should:

Run a forward pass on the model with the dataset prompts (i.e. the

.promptsattribute), using thennsightsyntax we’ve demonstrated previously,Return a tuple of the model’s output (i.e. a list of its string-token completions, one for each prompt in the batch) and the residual stream value at the end of layer

layer(e.g. iflayer = -1, this means the final value of the residual stream before we convert into logits).

You should only return the residual stream values for the very last sequence position in each prompt, i.e. the last -1 token (where the model makes the antonym prediction), and same for the completions.

Help - I’m not sure how to run (and index into) a batch of inputs.

If we pass a list of strings to the generator.invoke function, this will be tokenized with padding automatically.

The type of padding which is applied is left padding, meaning if you index at sequence position -1, this will get the final token in the prompt for all prompts in the list, even if the prompts have different lengths.

[30]:

def calculate_h(model: LanguageModel, dataset: ICLDataset, layer: int = -1) -> tuple[list[str], Tensor]:

"""

Averages over the model's hidden representations on each of the prompts in `dataset` at layer `layer`, to produce

a single vector `h`.

Inputs:

model: LanguageModel

the transformer you're doing this computation with

dataset: ICLDataset

the dataset whose prompts `dataset.prompts` you're extracting the activations from (at the last seq pos)

layer: int

the layer you're extracting activations from

Returns:

completions: list[str]

list of the model's next-token predictions (i.e. the strings the model predicts to follow the last token)

h: Tensor

average hidden state tensor at final sequence position, of shape (d_model,)

"""

raise NotImplementedError()

tests.test_calculate_h(calculate_h, model)

All tests in `test_calculate_h` passed.

Solution

def calculate_h(model: LanguageModel, dataset: ICLDataset, layer: int = -1) -> tuple[list[str], Tensor]:

"""

Averages over the model's hidden representations on each of the prompts in `dataset` at layer `layer`, to produce

a single vector `h`.

Inputs:

model: LanguageModel

the transformer you're doing this computation with

dataset: ICLDataset

the dataset whose prompts `dataset.prompts` you're extracting the activations from (at the last seq pos)

layer: int

the layer you're extracting activations from

Returns:

completions: list[str]

list of the model's next-token predictions (i.e. the strings the model predicts to follow the last token)

h: Tensor

average hidden state tensor at final sequence position, of shape (d_model,)

"""

with model.trace(dataset.prompts, remote=REMOTE):

h = model.transformer.h[layer].output[0][:, -1].mean(dim=0).save()

logits = model.lm_head.output[:, -1]

next_tok_id = logits.argmax(dim=-1).save()

completions = model.tokenizer.batch_decode(next_tok_id)

return completions, h

We’ve provided you with a helper function, which displays the model’s output on the antonym dataset (and highlights the examples where the model’s prediction is correct). Note, we’re using the repr function, because a lot of the completions are line breaks, and this helps us see them more clearly!

If the antonyms dataset was constructed well, you should find that the model’s completion is correct most of the time, and most of its mistakes are either copying (e.g. predicting wet -> wet rather than wet -> dry) or understandable completions which shouldn’t really be considered mistakes (e.g. predicting right -> left rather than right -> wrong). If we were being rigorous, we’d want to filter this dataset to make sure it only contains examples where the model can correctly

perform the task - but for these exercises, we won’t worry about this.

[31]:

def display_model_completions_on_antonyms(

model: LanguageModel,

dataset: ICLDataset,

completions: list[str],

num_to_display: int = 20,

) -> None:

table = Table(

"Prompt (tuple representation)",

"Model's completion\n(green=correct)",

"Correct completion",

title="Model's antonym completions",

)

for i in range(min(len(completions), num_to_display)):

# Get model's completion, and correct completion

completion = completions[i]

correct_completion = dataset.completions[i]

correct_completion_first_token = model.tokenizer.tokenize(correct_completion)[0].replace("Ġ", " ")

seq = dataset.seqs[i]

# Color code the completion based on whether it's correct

is_correct = completion == correct_completion_first_token

completion = f"[b green]{repr(completion)}[/]" if is_correct else repr(completion)

table.add_row(str(seq), completion, repr(correct_completion))

rprint(table)

# Get uncorrupted dataset

dataset = ICLDataset(ANTONYM_PAIRS, size=20, n_prepended=2)

# Getting it from layer 12, as in the description in section 2.1 of paper

model_completions, h = calculate_h(model, dataset, layer=12)

# Displaying the output

display_model_completions_on_antonyms(model, dataset, model_completions)

Model's antonym completions ┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┓ ┃ ┃ Model's completion ┃ ┃ ┃ Prompt (tuple representation) ┃ (green=correct) ┃ Correct completion ┃ ┡━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┩ │ (right, left), (maximum, minimum), melt -> │ ' melt' │ ' freeze' │ │ (minimum, maximum), (old, new), punishment -> │ ' reward' │ ' reward' │ │ (arrogant, humble), (blunt, sharp), compulsory -> │ ' optional' │ ' voluntary' │ │ (inside, outside), (freeze, melt), full -> │ ' empty' │ ' empty' │ │ (reject, accept), (awake, asleep), dusk -> │ ' dawn' │ ' dawn' │ │ (invisible, visible), (punishment, reward), heavy -> │ ' light' │ ' light' │ │ (victory, defeat), (forward, backward), young -> │ ' old' │ ' old' │ │ (up, down), (compulsory, voluntary), right -> │ ' wrong' │ ' wrong' │ │ (open, closed), (domestic, foreign), brave -> │ ' cowardly' │ ' cowardly' │ │ (under, over), (past, future), increase -> │ ' decrease' │ ' decrease' │ │ (inside, outside), (melt, freeze), over -> │ ' under' │ ' under' │ │ (solid, liquid), (backward, forward), open -> │ ' closed' │ ' closed' │ │ (optimist, pessimist), (invisible, visible), brave -> │ ' cowardly' │ ' cowardly' │ │ (noisy, quiet), (sell, buy), north -> │ ' south' │ ' south' │ │ (guilty, innocent), (birth, death), victory -> │ ' defeat' │ ' defeat' │ │ (answer, question), (noisy, quiet), ancient -> │ ' modern' │ ' modern' │ │ (on, off), (success, failure), flexible -> │ ' rigid' │ ' rigid' │ │ (junior, senior), (arrive, depart), punishment -> │ ' reward' │ ' reward' │ │ (loose, tight), (learn, teach), new -> │ ' new' │ ' old' │ │ (introduce, remove), (deficiency, quality), wet -> │ ' wet' │ ' dry' │ └───────────────────────────────────────────────────────┴────────────────────┴────────────────────┘

Using multiple invokes#

Another cool feature of nnsight is the ability to run multiple different batches through the model at once (or the same batch multiple times) in a way which leads to very clean syntax for doing causal interventions. Rather than doing something like this:

with model.trace(inputs, remote=REMOTE):

# some causal interventions

we can write a double-nested context manager:

with model.trace(remote=REMOTE) as tracer:

with tracer.invoke(inputs):

# some causal interventions

with tracer.invoke(other_inputs):

# some other causal interventions

Both inputs will be run together in parallel, and proxies defined within one tracer.invoke block can be used in another. A common use-case is to have clean and corrupted inputs, so we can patch from one to the other and get both outputs all in a single forward pass:

with model.trace(remote=REMOTE) as tracer:

with tracer.invoke(clean_inputs):

# extract clean activations

clean_activations = model.transformer.h[10].output[0]

with tracer.invoke(corrupted_inputs):

# patch clean into corrupted

model.transformer.h[10].output[0][:] = clean_activations

You’ll do something like this in a later exercise. However for your first exercise (immediately below), you’ll only be intervening with vectors that are defined outside of your context manager.

One important thing to watch out for - make sure you’re not using your proxy before it’s being defined! For example, if you were extracting clean_activations from model.transformer.h[10] but then intervening with it on model.transformer.h[9], this couldn’t be done in parallel (you’d need to first extract the clean activations, then run the patched forward pass). Doing this should result in a warning message, but may pass silently in some cases - so you need to be extra

vigilant!

Exercise - intervene with \(h\)#

Difficulty: 🔴🔴🔴⚪⚪ Importance: 🔵🔵🔵🔵⚪ You should spend up to 10-15 minutes on this exercise.

You should fill in the function intervene_with_h below. This will involve:

Run two forward passes (within the same context manager) on a zero-shot dataset:

One with no intervention (i.e. the residual stream is unchanged),

One with an intervention using

h(i.e.his added to the residual stream at the layer it was taken from).

Return the completions for no intervention and intervention cases respectively (see docstring).

The diagram below shows how all of this should work, when combined with the calculate_h function.

Hint - you can use tokenizer.batch_decode to turn a list of tokens into a list of strings.

Help - I’m not sure how best to get both the no-intervention and intervention completions.

You can use with tracer.invoke... more than once within the same context manager, in order to add to your batch. This will eventually give you output of shape (2*N, seq_len), which can then be indexed and reshaped to get the completions in the no intervention & intervention cases respectively.

Help - I’m not sure how to intervene on the hidden state.

First, you can define the tensor of hidden states (i.e. using .output[0], like you’ve done before).

Then, you can add to this tensor directly (or add to some indexed version of it). You can use inplace operations (i.e. tensor += h) or redefining the tensor (i.e. tensor = tensor + h); either work.

[33]:

def intervene_with_h(

model: LanguageModel,

zero_shot_dataset: ICLDataset,

h: Tensor,

layer: int,

remote: bool = REMOTE,

) -> tuple[list[str], list[str]]:

"""

Extracts the vector `h` using previously defined function, and intervenes by adding `h` to the

residual stream of a set of generated zero-shot prompts.

Inputs:

model: the model we're using to generate completions

zero_shot_dataset: the dataset of zero-shot prompts which we'll intervene on, using the `h`-vector

h: the `h`-vector we'll be adding to the residual stream

layer: the layer we'll be extracting the `h`-vector from

remote: whether to run the forward pass on the remote server (used for running test code)

Returns:

completions_zero_shot: list of string completions for the zero-shot prompts, without intervention

completions_intervention: list of string completions for the zero-shot prompts, with h-intervention

"""

raise NotImplementedError()

tests.test_intervene_with_h(intervene_with_h, model, h, ANTONYM_PAIRS, REMOTE)

Running your `intervene_with_h` function...

Running `solutions.intervene_with_h` (so we can compare outputs) ...

Comparing the outputs...

All tests in `test_intervene_with_h` passed.

Solution

def intervene_with_h(

model: LanguageModel,

zero_shot_dataset: ICLDataset,

h: Tensor,

layer: int,

remote: bool = REMOTE,

) -> tuple[list[str], list[str]]:

"""

Extracts the vector `h` using previously defined function, and intervenes by adding `h` to the

residual stream of a set of generated zero-shot prompts.

Inputs:

model: the model we're using to generate completions

zero_shot_dataset: the dataset of zero-shot prompts which we'll intervene on, using the `h`-vector

h: the `h`-vector we'll be adding to the residual stream

layer: the layer we'll be extracting the `h`-vector from

remote: whether to run the forward pass on the remote server (used for running test code)

Returns:

completions_zero_shot: list of string completions for the zero-shot prompts, without intervention

completions_intervention: list of string completions for the zero-shot prompts, with h-intervention

"""

with model.trace(remote=remote) as tracer:

# First, run a forward pass where we don't intervene, just save token id completions

with tracer.invoke(zero_shot_dataset.prompts):

token_completions_zero_shot = model.lm_head.output[:, -1].argmax(dim=-1).save()

# Next, run a forward pass on the zero-shot prompts where we do intervene

with tracer.invoke(zero_shot_dataset.prompts):

# Add the h-vector to the residual stream, at the last sequence position

hidden_states = model.transformer.h[layer].output[0]

hidden_states[:, -1] += h

# Also save completions

token_completions_intervention = model.lm_head.output[:, -1].argmax(dim=-1).save()

# Decode to get the string tokens

completions_zero_shot = model.tokenizer.batch_decode(token_completions_zero_shot)

completions_intervention = model.tokenizer.batch_decode(token_completions_intervention)

return completions_zero_shot, completions_intervention

Run the code below to calculate completions for the function.

Note, it’s very important that we set a different random seed for the zero shot dataset, otherwise we’ll be intervening on examples which were actually in the dataset we used to compute :math:`h`!

[34]:

layer = 12

dataset = ICLDataset(ANTONYM_PAIRS, size=20, n_prepended=3, seed=0)

zero_shot_dataset = ICLDataset(ANTONYM_PAIRS, size=20, n_prepended=0, seed=1)

# Run previous function to get h-vector

h = calculate_h(model, dataset, layer=layer)[1]

# Run new function to intervene with h-vector

completions_zero_shot, completions_intervention = intervene_with_h(model, zero_shot_dataset, h, layer=layer)

print("Zero-shot completions: ", completions_zero_shot)

print("Completions with intervention: ", completions_intervention)

Zero-shot completions: [' minimum', ' I', ' inside', ' reject', ' invisible', ' victory', ' up', ' open', ' under', ' inside', ' solid', '\n', ' noisy', ' guilty', ' yes', ' I', ' senior', ' loose', ' introduce', ' innocent']

Completions with intervention: [' maximum', ' arrogant', ' outside', ' reject', ' visible', ' victory', ' down', ' closed', ' under', ' outside', ' solid', ' optim', ' noisy', ' guilty', ' answer', ' on', ' senior', ' tight', ' introduce', ' guilty']

Next, run the code below to visualise the completions in a table. You should see:

~0% correct completions on the zero-shot prompt with no intervention, because the model usually just copies the first and only word in the prompt

~25% correct completions on the zero-shot prompt with intervention

[35]:

def display_model_completions_on_h_intervention(

dataset: ICLDataset,

completions: list[str],

completions_intervention: list[str],

num_to_display: int = 20,

) -> None:

table = Table(

"Prompt",

"Model's completion\n(no intervention)",

"Model's completion\n(intervention)",

"Correct completion",

title="Model's antonym completions",

)

for i in range(min(len(completions), num_to_display)):

completion_ni = completions[i]

completion_i = completions_intervention[i]

correct_completion = dataset.completions[i]

correct_completion_first_token = tokenizer.tokenize(correct_completion)[0].replace("Ġ", " ")

seq = dataset.seqs[i]

# Color code the completion based on whether it's correct

is_correct = completion_i == correct_completion_first_token

completion_i = f"[b green]{repr(completion_i)}[/]" if is_correct else repr(completion_i)

table.add_row(str(seq), repr(completion_ni), completion_i, repr(correct_completion))

rprint(table)

display_model_completions_on_h_intervention(zero_shot_dataset, completions_zero_shot, completions_intervention)

Model's antonym completions ┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┓ ┃ ┃ Model's completion ┃ Model's completion ┃ ┃ ┃ Prompt ┃ (no intervention) ┃ (intervention) ┃ Correct completion ┃ ┡━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┩ │ minimum -> │ ' minimum' │ ' maximum' │ ' maximum' │ │ arrogant -> │ ' I' │ ' arrogant' │ ' humble' │ │ inside -> │ ' inside' │ ' outside' │ ' outside' │ │ reject -> │ ' reject' │ ' reject' │ ' accept' │ │ invisible -> │ ' invisible' │ ' visible' │ ' visible' │ │ victory -> │ ' victory' │ ' victory' │ ' defeat' │ │ up -> │ ' up' │ ' down' │ ' down' │ │ open -> │ ' open' │ ' closed' │ ' closed' │ │ under -> │ ' under' │ ' under' │ ' over' │ │ inside -> │ ' inside' │ ' outside' │ ' outside' │ │ solid -> │ ' solid' │ ' solid' │ ' liquid' │ │ optimist -> │ '\n' │ ' optim' │ ' pessimist' │ │ noisy -> │ ' noisy' │ ' noisy' │ ' quiet' │ │ guilty -> │ ' guilty' │ ' guilty' │ ' innocent' │ │ answer -> │ ' yes' │ ' answer' │ ' question' │ │ on -> │ ' I' │ ' on' │ ' off' │ │ junior -> │ ' senior' │ ' senior' │ ' senior' │ │ loose -> │ ' loose' │ ' tight' │ ' tight' │ │ introduce -> │ ' introduce' │ ' introduce' │ ' remove' │ │ innocent -> │ ' innocent' │ ' guilty' │ ' guilty' │ └──────────────┴────────────────────┴────────────────────┴────────────────────┘

Exercise - combine the last two functions#

Difficulty: 🔴🔴🔴⚪⚪ Importance: 🔵🔵🔵⚪⚪ You should spend up to 10-15 minutes on this exercise.

One great feature of the nnsight library is its ability to parallelize forward passes and perform complex interventions within a single context manager.

In the code above, we had one function to extract the hidden states from the model, and another function where we intervened with those hidden states. But we can actually do both at once: we can compute \(h\) within our forward pass, and then intervene with it on a different forward pass (using our zero-shot prompts), all within the same model.trace context manager. In other words, we’ll be using ``with tracer.invoke…`` three times in this context manager.

You should fill in the calculate_h_and_intervene function below, to do this. Mostly, this should involve combining your calculate_h and intervene_with_h functions, and wrapping the forward passes in the same context manager (plus a bit of code rewriting).

Your output should be exactly the same as before (since the ICLDataset class is deterministic), hence we’ve not provided test functions in this case - you can just compare the table you get to the one before! However, this time around your code should run twice as fast, because you’re batching the operations of “compute \(h\)” and “intervene with \(h\)” together into a single forward pass.

Help - I’m not sure how to use the h vector inside the context manager.

You extract h the same way as before, but you don’t need to save it. It is kept as a proxy. You can still use it later in the context manager, just like it actually was a tensor.

You shouldn’t have to .save() anything inside your context manager, other than the token completions.

Help - If I want to add x vector to a slice of my hidden state tensor h, is h[slice]+=x the same as h2 = h[slice], h2 += x?

No, only h[slice]+=x does what you want. This is because when doing h2 = h[slice], h2 += x, the modification line h2 += x is no longer modifying the original tensor h, but a different tensorh2. In contrast, h[slice]+=x keeps the original tensor h in the modification line.

A good rule to keep in mind is: If you’re trying to modify a tensor some in-place operation, make sure that tensor is in the actual modification line!

[37]:

def calculate_h_and_intervene(

model: LanguageModel,

dataset: ICLDataset,

zero_shot_dataset: ICLDataset,

layer: int,

) -> tuple[list[str], list[str]]:

"""

Extracts the vector `h`, intervenes by adding `h` to the residual stream of a set of generated zero-shot prompts,

all within the same forward pass. Returns the completions from this intervention.

Inputs:

model: LanguageModel

the model we're using to generate completions

dataset: ICLDataset

the dataset of clean prompts from which we'll extract the `h`-vector

zero_shot_dataset: ICLDataset

the dataset of zero-shot prompts which we'll intervene on, using the `h`-vector

layer: int

the layer we'll be extracting the `h`-vector from

Returns:

completions_zero_shot: list[str]

list of string completions for the zero-shot prompts, without intervention

completions_intervention: list[str]

list of string completions for the zero-shot prompts, with h-intervention

"""

raise NotImplementedError()

dataset = ICLDataset(ANTONYM_PAIRS, size=20, n_prepended=3, seed=0)

zero_shot_dataset = ICLDataset(ANTONYM_PAIRS, size=20, n_prepended=0, seed=1)

completions_zero_shot, completions_intervention = calculate_h_and_intervene(

model, dataset, zero_shot_dataset, layer=layer

)

display_model_completions_on_h_intervention(zero_shot_dataset, completions_zero_shot, completions_intervention)

Model's antonym completions ┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┓ ┃ ┃ Model's completion ┃ Model's completion ┃ ┃ ┃ Prompt ┃ (no intervention) ┃ (intervention) ┃ Correct completion ┃ ┡━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┩ │ minimum -> │ ' minimum' │ ' maximum' │ ' maximum' │ │ arrogant -> │ ' arrogant' │ ' arrogant' │ ' humble' │ │ inside -> │ ' inside' │ ' outside' │ ' outside' │ │ reject -> │ ' reject' │ ' reject' │ ' accept' │ │ invisible -> │ ' invisible' │ ' visible' │ ' visible' │ │ victory -> │ ' victory' │ ' victory' │ ' defeat' │ │ up -> │ ' up' │ ' down' │ ' down' │ │ open -> │ ' open' │ ' closed' │ ' closed' │ │ under -> │ ' under' │ ' under' │ ' over' │ │ inside -> │ ' inside' │ ' outside' │ ' outside' │ │ solid -> │ ' solid' │ ' solid' │ ' liquid' │ │ optimist -> │ '\n' │ ' optim' │ ' pessimist' │ │ noisy -> │ ' noisy' │ ' noisy' │ ' quiet' │ │ guilty -> │ ' guilty' │ ' guilty' │ ' innocent' │ │ answer -> │ ' answer' │ ' answer' │ ' question' │ │ on -> │ ' I' │ ' on' │ ' off' │ │ junior -> │ ' junior' │ ' senior' │ ' senior' │ │ loose -> │ ' loose' │ ' tight' │ ' tight' │ │ introduce -> │ ' introduce' │ ' introduce' │ ' remove' │ │ innocent -> │ ' innocent' │ ' guilty' │ ' guilty' │ └──────────────┴────────────────────┴────────────────────┴────────────────────┘

Solution

def calculate_h_and_intervene(

model: LanguageModel,

dataset: ICLDataset,

zero_shot_dataset: ICLDataset,

layer: int,

) -> tuple[list[str], list[str]]:

"""

Extracts the vector `h`, intervenes by adding `h` to the residual stream of a set of generated zero-shot prompts,

all within the same forward pass. Returns the completions from this intervention.

Inputs:

model: LanguageModel

the model we're using to generate completions

dataset: ICLDataset

the dataset of clean prompts from which we'll extract the `h`-vector

zero_shot_dataset: ICLDataset

the dataset of zero-shot prompts which we'll intervene on, using the `h`-vector

layer: int

the layer we'll be extracting the `h`-vector from

Returns:

completions_zero_shot: list[str]

list of string completions for the zero-shot prompts, without intervention

completions_intervention: list[str]

list of string completions for the zero-shot prompts, with h-intervention

"""

with model.trace(remote=REMOTE) as tracer:

with tracer.invoke(dataset.prompts):

h = model.transformer.h[layer].output[0][:, -1].mean(dim=0)

with tracer.invoke(zero_shot_dataset.prompts):

clean_tokens = model.lm_head.output[:, -1].argmax(dim=-1).save()

with tracer.invoke(zero_shot_dataset.prompts):

hidden = model.transformer.h[layer].output[0]

hidden[:, -1] += h

intervene_tokens = model.lm_head.output[:, -1].argmax(dim=-1).save()

completions_zero_shot = tokenizer.batch_decode(clean_tokens)

completions_intervention = tokenizer.batch_decode(intervene_tokens)

return completions_zero_shot, completions_intervention

Exercise - compute change in accuracy#

Difficulty: 🔴🔴⚪⚪⚪ Importance: 🔵🔵🔵⚪⚪ You should spend up to 10-20 minutes on this exercise.

So far, all we’ve done is look at the most likely completions, and see what fraction of the time these were correct. But our forward pass doesn’t just give us token completions, it gives us logits too!

You should now rewrite the calculate_h_and_intervene function so that, rather than returning two lists of string completions, it returns two lists of floats containing the logprobs assigned by the model to the correct antonym in the no intervention / intervention cases respectively.

Help - I don’t know how to get the correct logprobs from the logits.

First, apply log softmax to the logits, to get logprobs.

Second, you can use tokenizer(dataset.completions)["input_ids"] to get the token IDs of the correct completions. (Gotcha - some words might be tokenized into multiple tokens, so make sure you’re just picking the first token ID for each completion.)

Note - we recommend doing all this inside the context manager, then saving and returning just the correct logprobs not all the logits (this means less to download from the server!).

[38]:

def calculate_h_and_intervene_logprobs(

model: LanguageModel,

dataset: ICLDataset,

zero_shot_dataset: ICLDataset,

layer: int,

) -> tuple[list[float], list[float]]:

"""

Extracts the vector `h`, intervenes by adding `h` to the residual stream of a set of generated zero-shot prompts,

all within the same forward pass. Returns the logprobs on correct tokens from this intervention.

Inputs:

model: LanguageModel

the model we're using to generate completions

dataset: ICLDataset

the dataset of clean prompts from which we'll extract the `h`-vector

zero_shot_dataset: ICLDataset

the dataset of zero-shot prompts which we'll intervene on, using the `h`-vector

layer: int

the layer we'll be extracting the `h`-vector from

Returns:

correct_logprobs: list[float]

list of correct-token logprobs for the zero-shot prompts, without intervention

correct_logprobs_intervention: list[float]

list of correct-token logprobs for the zero-shot prompts, with h-intervention

"""

raise NotImplementedError()

Solution

def calculate_h_and_intervene_logprobs(

model: LanguageModel,

dataset: ICLDataset,

zero_shot_dataset: ICLDataset,

layer: int,

) -> tuple[list[float], list[float]]:

"""

Extracts the vector `h`, intervenes by adding `h` to the residual stream of a set of generated zero-shot prompts,

all within the same forward pass. Returns the logprobs on correct tokens from this intervention.

Inputs:

model: LanguageModel

the model we're using to generate completions

dataset: ICLDataset

the dataset of clean prompts from which we'll extract the `h`-vector

zero_shot_dataset: ICLDataset

the dataset of zero-shot prompts which we'll intervene on, using the `h`-vector

layer: int

the layer we'll be extracting the `h`-vector from

Returns:

correct_logprobs: list[float]

list of correct-token logprobs for the zero-shot prompts, without intervention

correct_logprobs_intervention: list[float]

list of correct-token logprobs for the zero-shot prompts, with h-intervention

"""

correct_completion_ids = [toks[0] for toks in tokenizer(zero_shot_dataset.completions)["input_ids"]]

with model.trace(remote=REMOTE) as tracer:

with tracer.invoke(dataset.prompts):

h = model.transformer.h[layer].output[0][:, -1].mean(dim=0)

with tracer.invoke(zero_shot_dataset.prompts):

clean_logprobs = model.lm_head.output.log_softmax(dim=-1)[

range(len(zero_shot_dataset)), -1, correct_completion_ids

].save()

with tracer.invoke(zero_shot_dataset.prompts):

hidden = model.transformer.h[layer].output[0]

hidden[:, -1] += h

intervene_logprobs = model.lm_head.output.log_softmax(dim=-1)[

range(len(zero_shot_dataset)), -1, correct_completion_ids

].save()

return clean_logprobs, intervene_logprobs

When you run the code below, it will display the log-probabilities (highlighting green when they increase from the zero-shot case). You should find that in every sequence, the logprobs on the correct token increase in the intervention. This helps make something clear - even if the maximum-likelihood token doesn’t change, this doesn’t mean that the intervention isn’t having a significant effect.

[39]:

def display_model_logprobs_on_h_intervention(

dataset: ICLDataset,

correct_logprobs_zero_shot: list[float],

correct_logprobs_intervention: list[float],

num_to_display: int = 20,

) -> None:

table = Table(

"Zero-shot prompt",

"Model's logprob\n(no intervention)",

"Model's logprob\n(intervention)",

"Change in logprob",

title="Model's antonym logprobs, with zero-shot h-intervention\n(green = intervention improves accuracy)",

)

for i in range(min(len(correct_logprobs_zero_shot), num_to_display)):

logprob_ni = correct_logprobs_zero_shot[i]

logprob_i = correct_logprobs_intervention[i]

delta_logprob = logprob_i - logprob_ni

zero_shot_prompt = f"{dataset[i].x[0]:>8} -> {dataset[i].y[0]}"

# Color code the logprob based on whether it's increased with this intervention

is_improvement = delta_logprob >= 0

delta_logprob = f"[b green]{delta_logprob:+.2f}[/]" if is_improvement else f"{delta_logprob:+.2f}"

table.add_row(zero_shot_prompt, f"{logprob_ni:.2f}", f"{logprob_i:.2f}", delta_logprob)

rprint(table)

dataset = ICLDataset(ANTONYM_PAIRS, size=20, n_prepended=3, seed=0)

zero_shot_dataset = ICLDataset(ANTONYM_PAIRS, size=20, n_prepended=0, seed=1)

correct_logprobs_zero_shot, correct_logprobs_intervention = calculate_h_and_intervene_logprobs(

model, dataset, zero_shot_dataset, layer=layer

)

display_model_logprobs_on_h_intervention(

zero_shot_dataset, correct_logprobs_zero_shot, correct_logprobs_intervention

)

Model's antonym logprobs, with zero-shot h-intervention (green = intervention improves accuracy) ┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┓ ┃ ┃ Model's logprob ┃ Model's logprob ┃ ┃ ┃ Zero-shot prompt ┃ (no intervention) ┃ (intervention) ┃ Change in logprob ┃ ┡━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┩ │ minimum -> maximum │ -3.47 │ -1.12 │ +2.34 │ │ arrogant -> humble │ -6.19 │ -3.92 │ +2.27 │ │ inside -> outside │ -3.38 │ -0.88 │ +2.50 │ │ reject -> accept │ -3.44 │ -1.77 │ +1.67 │ │ invisible -> visible │ -3.61 │ -1.68 │ +1.93 │ │ victory -> defeat │ -4.31 │ -2.16 │ +2.16 │ │ up -> down │ -2.73 │ -0.58 │ +2.16 │ │ open -> closed │ -5.62 │ -1.61 │ +4.00 │ │ under -> over │ -6.31 │ -4.19 │ +2.12 │ │ inside -> outside │ -3.38 │ -0.88 │ +2.50 │ │ solid -> liquid │ -5.12 │ -3.19 │ +1.94 │ │ optimist -> pessimist │ -6.44 │ -3.39 │ +3.05 │ │ noisy -> quiet │ -5.00 │ -3.00 │ +2.00 │ │ guilty -> innocent │ -4.28 │ -2.31 │ +1.97 │ │ answer -> question │ -4.62 │ -3.75 │ +0.88 │ │ on -> off │ -5.66 │ -3.81 │ +1.84 │ │ junior -> senior │ -2.72 │ -0.66 │ +2.06 │ │ loose -> tight │ -3.52 │ -1.63 │ +1.88 │ │ introduce -> remove │ -7.03 │ -5.84 │ +1.19 │ │ innocent -> guilty │ -3.00 │ -1.43 │ +1.57 │ └───────────────────────┴───────────────────┴─────────────────┴───────────────────┘

3️⃣ Function Vectors#

Learning Objectives

Define a metric to measure the causal effect of each attention head on the correct performance of the in-context learning task

Understand how to rearrange activations in a model during an

nnsightforward pass, to extract activations corresponding to a particular attention headLearn how to use

nnsightfor multi-token generation

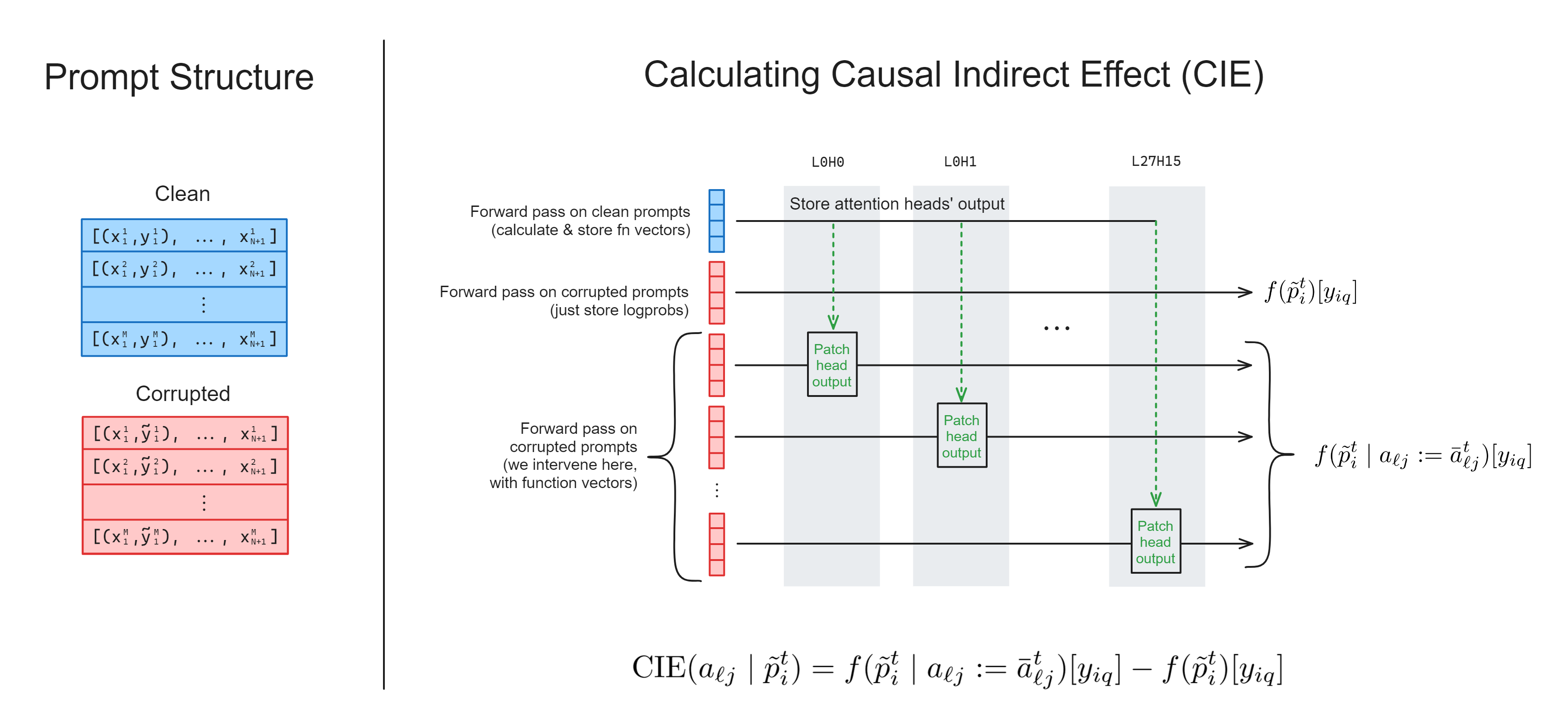

In this section, we’ll replicate the crux of the paper’s results, by identifying a set of attention heads whose outputs have a large effect on the model’s ICL performance, and showing we can patch with these vectors to induce task-solving behaviour on randomly shuffled prompts.

We’ll also learn how to use nnsight for multi-token generation, and steer the model’s behaviour. There exist exercises where you can try this out for different tasks, e.g. the Country-Capitals task, where you’ll be able to steer the model to complete prompts like "When you think of Netherlands, you usually think of" by talking about Amsterdam.

Note - this section structurally follows sections 2.2, 2.3 and some of section 3 from the function vectors paper.

Here, we’ll move from thinking about residual stream states to thinking about the output of specific attention heads.

Extracting & using FVs#

A note on out_proj#

First, a bit of a technical complication. Most HuggingFace models don’t have the nice attention head representations. What we have is the linear layer out_proj which implicitly combines the “projection per attention head” and the “sum over attention head” operations (if you can’t see how this is possible, see the section “Attention Heads are Independent and Additive” from Anthropic’s Mathematical Framework).

This presents some question for us, when it comes to causal interventions on attention heads. Use the dropdowns below to read them answer these questions (they’ll be important for the coming exercises).

If we want to do a causal intervention on a particular head, should we intervene on z (the input of out_proj) or on attn_output (the output of out_proj) ?

We should intervene on z, because we can just rearrange the z tensor of shape (batch, seq, d_model) into (batch, seq, n_heads, d_head), in other words separating out all the heads. On the other hand, we can’t do this with the attn_output because it’s already summed over heads and we can’t separate them out.

How could we get the attn_output vector for a single head, if we had the ability to access model weights within our context managers?

We can take a slice of the z tensor corresponding to a single attention head:

z.reshape(batch, seq, n_heads, d_head)[:, :, head_idx]

and we can take a slice of the out_proj weight matrix corresponding to a single attention head (remember that PyTorch stores linear layers in the shape (out_feats, in_feats)):

out_proj.weight.rearrange(d_model, n_heads, d_head)[:, head_idx]

then finally we can multiply these together.

How could we get the attn_output vector for a single head, if we didn’t have the ability to access model weights within our context managers? (This is currently the case for nnsight, since having access to the weights could allow users to change them!).

We can be a bit clever, and ablate certain heads in the z vector before passing it through the output projection:

# ablate all heads except #2 (using a cloned activation)

heads_to_ablate = [0, 1, 3, 4, ...]

z_ablated = z.reshape(batch, seq, n_heads, d_head).clone()

z_ablated[:, :, heads_to_ablate] = 0

# save the output

attn_head_output = out_proj(z_ablated)

Illustration:

Note - this would actually fail if out_proj had a bias, because we want to just get an attention head’s output, not the bias term as well. But if you look at the documentation page you’ll see that out_proj doesn’t have a bias term, so we’re all good!

Exercise - implement calculate_fn_vectors_and_intervene#

Difficulty: 🔴🔴🔴🔴🔴 Importance: 🔵🔵🔵🔵🔵 You should spend up to 30-60 minutes on this exercise.